|

19 May 2007 04:25 SOMALIA WATCH |

| SW News | |||||||||||||

DJIBOUTI JOURNALSomalia's 'Hebrews' See a Better DayBy IAN FISHER

"Even our young people," he said, "they are ashamed when you ask them what tribe they belong to. They will not say Yibir." Not much is known about the lineage of the Yibir, one of Somalia's "sab," or outcast, clans. But if Somalis succeed in creating a new central government -- as they have been trying to do since March -- the Yibir will for the first time taste political legitimacy and respect. In the 225-member assembly envisioned for a new Somalia, the Yibir get one seat. A conscious effort is being made to broaden political power in Somalia, traditionally held by old men from the four major clans. In the new assembly, women, the bedrock of Somali economic and family life, have been allocated 25 seats. Minority clans like the Yibir, Midgan and Tomal will have 24 seats, if the assembly is ever translated from a nice idea at a peace conference here in neighboring Djibouti to an actual government in Somalia, which has been without one since 1991. "This is the most broad-based process that Somalia has ever known," said David Stephen, the representative of Kofi Annan, the United Nations secretary general, at the peace talks. "Never before have women and minorities taken part in discussions about their country." The question is whether this means anything. It is far from certain that any new government will ever actually sit in Somalia, though hopes are high. Perhaps more important is whether the elderly men from the major clans will cede any of their authority. Mr. Stephen said some men bluntly say that they "are only doing this to please the United Nations." But still the minority groups, who prefer to be called the Alliance, and women are talking about the power they theoretically hold if they vote as a bloc.

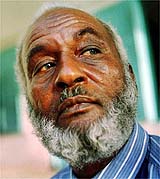

The top positions in any new government are likely to be doled out to the major clans, and any clan that makes alliances with the women and minorities in the assembly is more likely to win. "We have to have one voice and one interest as women," said Asha Haji Elmi, leader of the women delegates to the conference. She conceded that there would be pressure for women to vote with their clans rather than as women. Twenty of the women's seats are assigned to the four major clans and the remaining five to the minority clans. "It's difficult," she said, "but we have to overcome the obstacles." It is, at any rate, a high-minded exercise, pushed strongly by the peace conference's host, President Ismael Omar Gelleh of Djibouti -- though Somalis are quick to point out that Mr. Gelleh's own government is not nearly so liberal as his vision for Somalia's. "It is not in our tradition," said Mahmoud Imam Omar, an elder in one of the major clans, the Hawiye, speaking of the inclusion of women. "President Gelleh has made us do it. But we have accepted it." A Somali businessman, Muhammad Ali Muhammad, said it was an experiment worth trying. "We have seen how the men have devastated the country," he said. "So maybe the women and minority groups would be better." A new government is, of course, no guarantee of equality. Then again, the Yibir do not have much to begin with. Mr. Hersi, 68, who has been the elected leader of the Yibir for 22 years, was asked to speak at one of the opening sessions of the peace conference two months ago. He noted that the Yibir had suffered terribly during the years of war but wanted badly to forgive and move on. "In the civil war I lost my son, my wife, my brother, my dignity and my self-respect," he told the delegates. "But still I have come here to work for reconciliation." Part of the bad treatment, he concedes, is the support of many Yibir for the dictator Muhammad Siad Barre. When he was overthrown in 1991, Mr. Hersi fled the country with surviving members of his family to live in Nairobi, Kenya's capital. But part of it is simply that they are one of the low castes of Somalis, and particularly that they are believed to be ethnic Jews in a strongly Muslim country. "We were never given our rights," he said. For many years the Yibir were forbidden to be educated, and Mr. Hersi says he can barely spell his name. They do work that is considered to be base, like metalworking and shoemaking. Traditionally many earned money through the Somali belief, stretching back perhaps centuries, that it is lucky to give the Yibir a small amount of money when a son is born or at a marriage. Mr. Hersi cannot say exactly how or when his ancestors made it to Somalia, though he believes that about 25,000 Yibir live there and in neighboring countries like Ethiopia, Djibouti and Kenya. Stories passed down from his forefathers have it that they came as Arabic-speaking teachers more than 1,000 years ago. He said there was no relation between them and the Jews of neighboring Ethiopia, many of whom still practice Judaism. It is hard to say exactly how the Yibir are Jews, or why they treated so badly because of it. The Yibir not only know nothing about Judaism, but they also say they have no intention of converting or, like the Ethiopian Jews, seeking resettlement in Israel. "That would only make more problems," said another Yibir, Muhammad Ali Hassan, a trader in the emirate of Dubai on the Persian Gulf. The process of getting their one seat has been typically difficult. Mr. Hersi said he had never received an invitation even to come to the conference, though he made it here with the help of the United Nations. In negotiations with other outcast clans, the Yibir originally were given two seats in Parliament, but a few days ago, one was stripped from them. Still, he said, one seat is a start. "Before we had nothing," he said. "This is the beginning, the first step." [ News] |

|||||||||||||